The python facilities for Crystal Field calculations are available in Mantid from module CrystalField. There are two main classes the module provides: CrystalFiled that defines various properties of a crystal field and CrystalFieldFit that manages the fitting process.

A crystal field computation starts with creating an instance of the CrystalField class. The constructor has two mandatory arguments: Ion - a symbolic name of the ion, and Symmetry - a name of the symmetry group of the field. The rest of the parameters are optional.

Possible values for the Ion argument:

Ce, Pr, Nd, Pm, Sm, Eu, Gd, Tb, Dy, Ho, Er, Tm, Yb

These are the trivalent rare-earth ions. For other rare earth ions, use the equivalent trivalent ion based on the number of f-electrons in the outer shell (e.g. for Pr4+ (4f1) use Ce). The rare earth ions sets the correct value of the Lande g-factor. In addition, a pure spin ion with arbitrary (but half-integral) S (or J) values are also supported using the syntax: Ion=S<n> where <n> is an integer or half-integer value, e.g. Ion=S2 or Ion=S1.5. In these cases, the g-factor is set to gJ = 2. The prefix letter can also be J instead of S, and lower case letters are also supported. (e.g. Ion=j1, Ion=s2.5 and Ion=J0.5 are all valid).

Allowed values for Symmetry:

C1, Ci, C2, Cs, C2h, C2v, D2, D2h, C4, S4, C4h, D4, C4v, D2d, D4h, C3,

S6, D3, C3v, D3d, C6, C3h, C6h, D6, C6v, D3h, D6h, T, Td, Th, O, Oh

The minimum code to create a crystal field object is:

from CrystalField import CrystalField

cf = CrystalField('Ce', 'C2v')

Names of the crystal field parameters have the form Bnn and IBnn where nn are two digits between 0 and 6. The Bnn is a real and the IBnn is an imaginary part of a complex parameter. If a parameter isn’t set explicitly its default value is 0. To set a parameter pass it to the CrystalField constructor as a keyword argument, e.g.:

cf = CrystalField('Ce', 'C2v', B20=0.37737, B22=3.9770)

An alternative way to set a parameter is to use the square brackets with a CrystalField object:

cf['B40'] = -0.031

Which can also be used to query the value of a parameter:

b = cf['B40']

CrystalFiled class has methods to calculate the Hamiltonian and its eigensystem:

# Calculate and return the Hamiltonian matrix as a 2D numpy array.

h = cf.getHamiltonian()

# Calculate and return the eigenvalues of the Hamiltonian as a 1D numpy array.

e = cf.getEigenvalues()

# Calculate and return the eigenvectors of the Hamiltonian as a 2D numpy array.

w = cf.getEigenvectors()

It is efficient to call the above methods multiple times as all the outputs are cached and the calculations are repeated only after a parameter changes.

To calculate a spectrum CrystalField needs to know the sample temperature and the shape of the peaks.

The temperature can be set either via a keyword argument Temperature of the constructor or using the Temperature property:

# Using the keyword argument

cf = CrystalField('Ce', 'C2v', B20=0.37737, B22=3.9770, Temperature=44)

# Using the property

cf.Temperature = 44

Knowing the temperature allows us to calculate a peak list: a list of transition energies and intensities.:

print cf.getPeakList()

The output is:

[[ 0.00000000e+00 2.44006198e+01 4.24977124e+01 1.80970926e+01 -2.44006198e+01]

[ 2.16711565e+02 8.83098530e+01 5.04430056e+00 1.71153708e-01 1.41609425e-01]]

The first row are the energies (in meV) and the second row are the integrated intensities (in milibarn per steradian).

The number of peaks that the function returns is controlled by two tolerance parameters: ToleranceEnergy and ToleranceIntensity. If a peak has an intensity below the value of ToleranceIntensity the peak is ignored. It two peaks have a difference in the energies smaller than ToleranceEnergy they are combined into a single peak.

If we set ToleranceIntensity of the above crystal field object to 1 mb/sr we’ll have only three peaks in the list:

cf.ToleranceIntensity = 1

print cf.getPeakList()

The new output:

[[ 0. 24.40061976 42.49771237]

[ 216.71156467 88.30985303 5.04430056]]

To calculate a spectrum we need to define a shape of each peak (peak profile function) and its default width (FWHM). The width can be set either via a keyword argument or a property with name FWHM. If the peak shape isn’t set the default of Lorentzian is assumed. To set a different shape use the PeakShape property:

cf.PeakShape = 'Gaussian'

cf.FWHM = 0.9

The values of PeakShape are expected to be names of Mantid peak fit functions. At the moment only Lorentzian and Gaussian can be used.

After the peak shape is defined a spectrum can be calculated:

sp = cf.getSpectrum()

The output is a tuple of two 1d numpy arrays (x, y) that can be used with matplotlib to plot:

pyplot.plot(*sp)

pyplot.show()

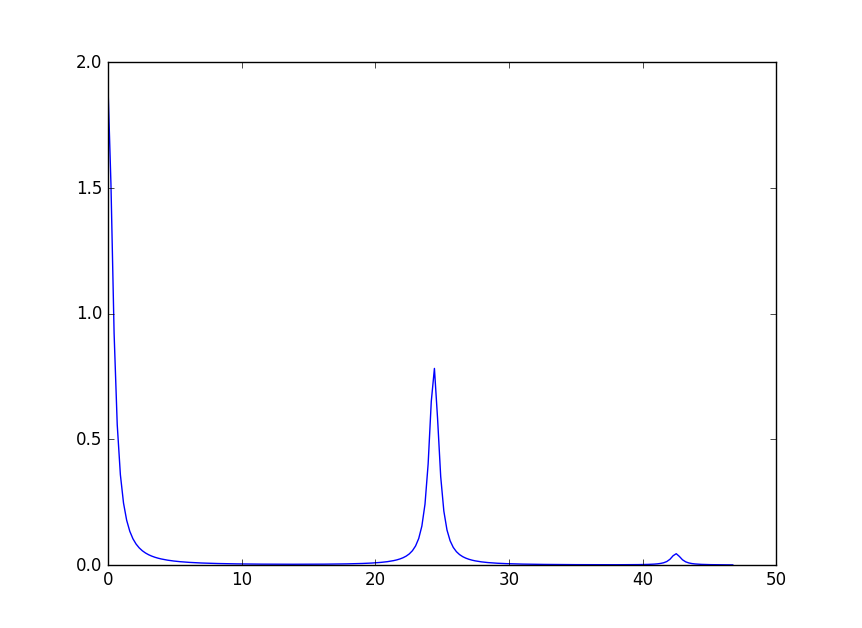

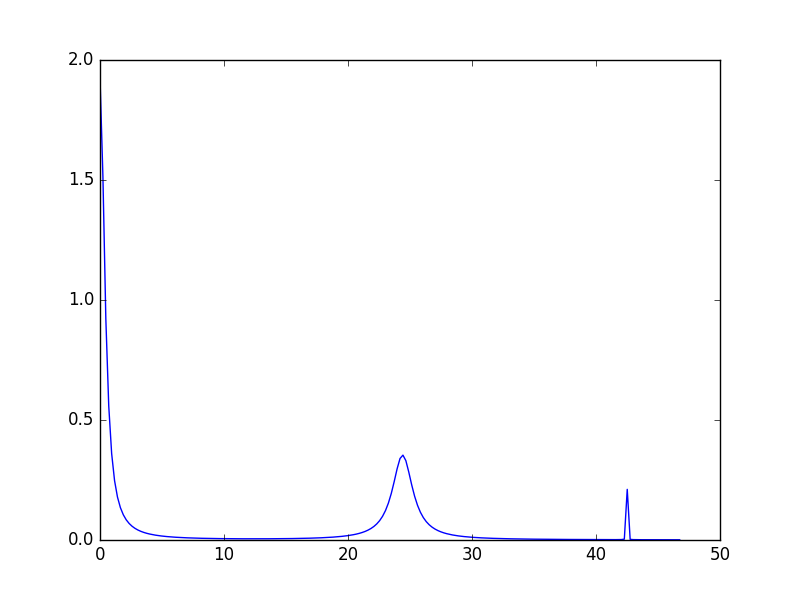

It is possible to change parameters of individual peaks separately. Note though that only the shape parameters can be changed, the peak centre and the integrated intensity are defined by the crystal field parameters. To change the width of a peak use the following syntax:

# If the peak shape is Gaussian

cf.peaks.param[1]['Sigma'] = 2.0

cf.peaks.param[2]['Sigma'] = 0.01

# If the peak shape is Lorentzian

cf.peaks.param[1]['FWHM'] = 2.0

cf.peaks.param[2]['FWHM'] = 0.01

The three peaks now have all different widths. The first peak (index 0) keeps the default value.

If called without arguments getSpectrum() determines automatically the range and number of the x-points. To have more control of how the spectrum is calculated a list (or numpy array) of x-values can be provided as a first argument to getSpectrum. Alternatively, the x-values can be taken from a workspace:

# Use a list for x-values

x = [0, 1, 2, 3, ...]

sp = cf.getSpectrum(x)

# Use the first spectrum of a workspace

sp = cf.getSpectrum(ws)

# Use the i-th spectrum of a workspace

sp = cf.getSpectrum(ws, i)

To plot a spectrum using MantidPlot’s graphing facilities CrystalField has method plot. It has the same arguments as getSpectrum and opens a window with a plot.

A background has two components: a peak and a general background function. Set a background using the background property:

from CrystalField import CrystalField, CrystalFieldFit, Background, Function

cf = CrystalField('Ce', 'C2v', B20=0.37737, B22=3.9770, B40=-0.031787, B42=-0.11611, B44=-0.12544,

Temperature=44.0, FWHM=1.1)

cf.background = Background(peak=Function('Gaussian', Height=10, Sigma=1),

background=Function('LinearBackground', A0=1.0, A1=0.01))

Here is an example of how to access the parameters of the background:

h = cf.background.peak.param['Height']

a1 = cf.background.background.param['A1']

Setting ties and constraints are done by calling the ties and constraints methods of the CrystalField class or its components. To Bnn parameters are tied by the CrystalField class directly specifying the tied parameter as a keyword argument:

cf.ties(B20=1.0, B40='B20/2')

The constraints are passed as strings containing expressions:

cf.constraints('1 < B22 <= 2', 'B22 < 4')

For the parameters of the background the syntax is the same but the methods are called on the background property:

cf.background.peak.ties(Height=10.1)

cf.background.peak.constraints('Sigma > 0')

cf.background.background.ties(A0=0.1)

cf.background.background.constraints('A1 > 0')

The names of the peak parameters both in ties and constraints must include the index of the peak to which they belong. Here we follow the naming convention of the CompositeFunction: f<n>.<name>, where <n> stands for an integer index staring at 0 and <name> is the name of the parameter. For example, f1.Sigma, f3.FWHM. Because names now contain the period symbol ‘.’ keyword arguments cannot be used. Instead we must pass a dictionary containing ties. The keys are parameter names and the values are the ties:

cf.peaks.ties({'f2.FWHM': '2*f1.FWHM', 'f3.FWHM': '2*f2.FWHM'})

Constraints are a list of strings:

cf.peaks.constraints('f0.FWHM < 2.2', 'f1.FWHM >= 0.1')

If a parameter of all peaks needs to be tied/constrained with the same expression then the following shortcut methods can be used:

cf.peaks.tieAll('Sigma=0.1', 3)

cf.peaks.constrainAll('0 < Sigma < 0.1', 4)

where the first argument is the general formula of the tie/constraint and the second is the number of peaks to apply to. There is also a version for a range of peak indices:

cf.peaks.tieAll('Sigma=f0.Sigma', 1, 3)

which is equivalent to:

cf.peaks.ties({'f1.Sigma': 'f0.Sigma', 'f2.Sigma': 'f0.Sigma', 'f3.Sigma': 'f0.Sigma'})

Resolution model here is a way to constrain widths of the peaks to realistic numbers which agree with a measured or calculated instrument resolution function. A model is a function that returns a FWHM for a peak centre. The Crystal Field python interface defines helper class ResolutionModel to help define and set resolution models.

To construct an instance of ResolutionModel one needs to provide up to four input parameters. The first parameter, model, is mandatory and can be either of the two

If the model is a tuple of two arrays then no additional parameters are required. If it’s a function then the rest of the parameters define how to tabulate this

function. xstart and xend define the interval of interpolation which must include all fitted peaks. The last argument is accuracy that defaults to

and defines an approximate desired accuracy of the approximation. The interval will be split until the largest error of the interpolation

is smaller than accuracy. Note that subdivision cannot go on to infinity as the number of points is limited by the class member ResolutionModel.max_model_size.

and defines an approximate desired accuracy of the approximation. The interval will be split until the largest error of the interpolation

is smaller than accuracy. Note that subdivision cannot go on to infinity as the number of points is limited by the class member ResolutionModel.max_model_size.

Example of setting a resolution model:

rm = ResolutionModel(([1, 2, 3, ...., 100], [0.1, 0.3, 0.35, ..., 2.1]))

cf = CrystalField('Ce', 'C2v', B20=0.37737, B22=3.9770, ..., Temperature=44.0, ResolutionModel=rm)

...

rm = ResolutionModel(my_func, xstart=0.0, xend=120.0, accuracy=0.01)

cf = CrystalField('Ce', 'C2v', B20=0.37737, B22=3.9770, ..., Temperature=44.0, ResolutionModel=rm)

When a resolution model is set the peak width will be constrained to have a value close to the model. The degree of deviation is controlled by the FWHMVariation parameter. It has the default of 0.1 and is an absolute maximum difference a width can have. If set to 0 the widths will be fixed to their calculated values (depending on the instant values of their peak centres). For example:

cf = CrystalField('Ce', 'C2v', B20=0.37737, B22=3.9770, ..., Temperature=44.0, ResolutionModel=rm, FWHMVariation=0.001)

A CrystalField object can be configured to work with multiple spectra. In this case some many of the object’s properties become lists. Here is an example of defining a CrystalField object with two spectra:

cf = CrystalField('Ce', 'C2v', B20=0.37737, B22=3.9770, B40=-0.031787, B42=-0.11611, B44=-0.12544,

Temperature=[44.0, 50], FWHM=[1.1, 0.9])

cf.PeakShape = 'Lorentzian'

cf.peaks[0].param[0]['FWHM'] = 1.11

cf.peaks[1].param[1]['FWHM'] = 1.12

cf.background = Background(peak=Function('Gaussian', Height=10, Sigma=0.3),

background=Function('FlatBackground', A0=1.0))

cf.background[1].peak.param['Sigma'] = 0.8

cf.background[1].background.param['A0'] = 1.1

Note how Temperature, FWHM, peaks and background become lists. They must have the same size. Ties and constraints similarly change:

# The B parameters are common for all spectra - syntax doesn't change

cf.ties(B20=1.0, B40='B20/2')

cf.constraints('1 < B22 <= 2', 'B22 < 4')

# Backgrounds and peaks are different for different spectra - must be indexed

cf.background[0].peak.ties(Height=10.1)

cf.background[0].peak.constraints('Sigma > 0.1')

cf.background[1].peak.ties(Height=20.2)

cf.background[1].peak.constraints('Sigma > 0.2')

cf.peaks[1].tieAll('FWHM=2*f1.FWHM', 2, 5)

cf.peaks[0].constrainAll('FWHM < 2.2', 1, 4)

The resolution model also needs to be initialised from a list:

x0, y0, x1, y1 = [ ... ], [ ... ], [ ... ], [ ... ]

rm = ResolutionModel([(x0, y0), (x1, y1)])

# or

rm = ResolutionModel([func0, func1], 0, 100, accuracy = 0.01)

To calculate a spectrum call the same method getSpectrum but pass the spectrum index as its first parameter:

# Calculate second spectrum, use the generated x-values

sp = cf.getSpectrum(1)

# Calculate third spectrum, use a list for x-values

x = [0, 1, 2, 3, ...]

sp = cf.getSpectrum(2, x)

# Calculate second spectrum, use the first spectrum of a workspace

sp = cf.getSpectrum(1, ws)

# Calculate first spectrum, use the i-th spectrum of a workspace

sp = cf.getSpectrum(0, ws, i)

Note that the attributes Temperature, FWHM, peaks and background may be set separately from the constructor, e.g.:

cf = CrystalField('Ce', 'C2v', B20=0.37737, B22=3.9770, B40=-0.031787, B42=-0.11611, B44=-0.12544)

cf.Temperature = [5, 50]

However, each time that Temperature is set, if it defines a different number of spectra from the previous value (e.g. if Temperature was initially empty or None and is then defined as in the example above, or if Temperature was initially a scalar value but is then redefined to be a list or vice versa), then all Ties, Constraints, FWHM and peaks parameters are cleared. Any crystal field parameters previously defined will be retained, however.

If there are multiple ions define CrystalField objects for each ion separately then add them together:

params = {'B20': 0.377, 'B22': 3.9, 'B40': -0.03, 'B42': -0.116, 'B44': -0.125,

'Temperature': [44.0, 50], 'FWHM': [1.1, 0.9]}

cf1 = CrystalField('Ce', 'C2v', **params)

cf2 = CrystalField('Pr', 'C2v', **params)

cf = cf1 + cf2

The expression that combines the CrystalField objects also defines the contributions of each site into the overall intensity. The higher the coefficient of the object in the expression the higher its relative contribution. For example:

cf = 2*cf1 + cf2

means that the intensity of cf1 should be twice that of cf2.

To fit the crystal field and peak parameters first create a CrystalField object as described above. Then create an instance (object) of the CrystalFieldFit class:

from CrystalField import CrystalFieldFit

# In case of a single spectrum (ws is a workspace)

fit = CrystalFieldFit(Model=cf, InputWorkspace=ws)

# Or for multiple spectra

fit = CrystalFieldFit(Model=cf, InputWorkspace=[ws1, ws2])

Then call fit() method:

fit.fit()

After fitting finishes the CrystalField object updates automatically and contains new fitted parameter values.

If the initial values of the fitting parameters are not known they can be estimated using estimate_parameters() method. It randomly searches the parameter space in a given region such that the calculated spectra are as close to the fit data as possible. The method uses EstimateFitParameters internally. See algorithm’s description for the available properties. Here is an example of a fit with initial estimation:

from CrystalField.fitting import makeWorkspace

from CrystalField import CrystalField, CrystalFieldFit, Background, Function

# Create some crystal field data

origin = CrystalField('Ce', 'C2v', B20=0.37737, B22=3.9770, B40=-0.031787, B42=-0.11611, B44=-0.12544,

Temperature=44.0, FWHM=1.1)

x, y = origin.getSpectrum()

ws = makeWorkspace(x, y)

# Define a CrystalField object with parameters slightly shifted.

cf = CrystalField('Ce', 'C2v', B20=0, B22=0, B40=0, B42=0, B44=0,

Temperature=44.0, FWHM=1.0, ResolutionModel=([0, 100], [1, 1]), FWHMVariation=0)

# Set any ties on the field parameters.

cf.ties(B20=0.37737)

# Create a fit object

fit = CrystalFieldFit(cf, InputWorkspace=ws)

# Find initial values for the field parameters.

# You need to define the energy splitting and names of parameters to estimate.

# Optionally additional constraints can be set on tied parameters (eg, peak centres).

fit.estimate_parameters(EnergySplitting=50,

Parameters=['B22', 'B40', 'B42', 'B44'],

Constraints='20<f1.PeakCentre<45,20<f2.PeakCentre<45',

NSamples=1000)

print 'Returned', fit.get_number_estimates(), 'sets of parameters.'

# The first set (the smallest chi squared) is selected by default.

# Select a different parameter set if required

fit.select_estimated_parameters(3)

print cf['B22'], cf['B40'], cf['B42'], cf['B44']

# Run fit

fit.fit()

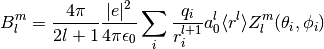

Alternatively, the Point Charge Model may be used to calculate the crystal field parameters. In this case, the

crystal field interaction is assumed to be purely electrostatic. At an infinite distance away from an ion, or

analogously, at a nonzero distance from an ion of infinitesimal extend (a point charge), the charge in free space

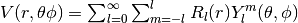

is zero, so Gauss’s law becomes  which is Laplace’s equation. The solution of this is a

multipole expansion, a sum of spherical harmonic functions:

which is Laplace’s equation. The solution of this is a

multipole expansion, a sum of spherical harmonic functions:

. In the limit of infinite

. In the limit of infinite

,

,  . The radial term is the crystal field parameters, and the angular term

(spherical harmonics in this case) are the crystal field operators.

. The radial term is the crystal field parameters, and the angular term

(spherical harmonics in this case) are the crystal field operators.

One should now note that the quantities noted above are generally complex. In order to have real valued parameters,

Stevens chose to use the tesseral harmonics  instead of the spherical harmonics for the

angular part. These functions are simply the hermitian combinations of spherical harmonics of the same rank

instead of the spherical harmonics for the

angular part. These functions are simply the hermitian combinations of spherical harmonics of the same rank  and opposite signed order

and opposite signed order  . (An alternative formulation by Wybourne uses the original spherical harmonics)

. (An alternative formulation by Wybourne uses the original spherical harmonics)

In Mantid we use the Stevens convention, as common in the neutron scattering literature. The user should note that the convention amongst optical spectroscopists is that of Wybourne.

A derivation of the point charge energy can be found in many text books (e.g. Morrison), but will not be detailed here, where only the final result is given:

where  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  are the charge (in units of the elemental

charge

are the charge (in units of the elemental

charge  ) and relative polar coordinates of the

) and relative polar coordinates of the  point charge from the magnetic ion;

point charge from the magnetic ion;

is the Bohr radius,

is the Bohr radius,  is the

is the  order expectation value

of the radial wavefunction of the magnetic ion and

order expectation value

of the radial wavefunction of the magnetic ion and  is the permitivity of free space (note this

equation is in SI units; many older texts use cgs units, but this does not matter because the value is eventually

converted to energy units of meV, rather than Joules or ergs).

is the permitivity of free space (note this

equation is in SI units; many older texts use cgs units, but this does not matter because the value is eventually

converted to energy units of meV, rather than Joules or ergs).

In order to calculate the point charge model crystal field parameters a set of charged ligands around the magnetic ion has to be given. This may be done either directly, as a list of 4-element lists [charge, pos_x, pos_y, pos_z]:

from CrystalField import PointCharge

axial_pc_model = PointCharge([[-2, 0, 0, -4], [-2, 0, 0, 4]], 'Nd')

axial_blm = axial_pc_model.calculate()

print(axial_blm)

which represents a simple axial crystal field with charges at  away from a Nd ion in the

z-direction.

away from a Nd ion in the

z-direction.

Alternatively, the set of ligands may be calculated from a crystal structure and a maximum distance. For example, for a cubic crystal field in the perovskite structure:

from CrystalField import PointCharge

from mantid.geometry import CrystalStructure

perovskite_structure = CrystalStructure('4 4 4 90 90 90', 'P m -3 m', 'Ce 0 0 0 1 0; Al 0.5 0.5 0.5 1 0; O 0.5 0.5 0 1 0')

cubic_pc_model = PointCharge(perovskite_structure, 'Ce', Charges={'Ce':3, 'Al':3, 'O':-2}, MaxDistance=7.5)

The syntax for the CrystalStructure object is given in the Crystal Structure concept page. Instead of the maximum distance, MaxDistance, in Angstrom, the maximum nth neighbour can be specified with:

cubic_pc_model = PointCharge(perovskite_structure, 'Ce', Charges={'Ce':3, 'Al':3, 'O':-2}, Neighbour=2)

note that this might result in a slightly slower calculation, because internally, a maximum distance much greater the nth neighbour is set and then all neighbours up to n are found within this distance.

If a workspace with a defined crystal structure exists, it can be used instead of the CrystalStructure object. Other inputs remain the same. Finally, a CIF file can be given directly:

cif_pc_model = PointCharge('somecompound.cif')

This uses LoadCIF to parse the input CIF file. Note that LoadCIF changes the atom labels, so you should use the getIons() method to get the actual atom labels which PointCharge uses. E.g. using this cif file:

cif_pc_model = PointCharge('AMS_DATA.cif')

print(cif_pc_model.getIons())

gives:

{'O1': [0.125, 0.125, 0.375],

'O2': [0.125, 0.375, 0.375],

'Yb1': [0.25, 0.25, 0.25],

'Yb2': [0.021, 0.0, 0.25],

'Yb3': [0.542, 0.0, 0.25]}

You can then define the charges for each site, the magnetic ion and the maximum distance, and calculate:

cif_pc_model.Charges = {'O1':-2, 'O2':-2, 'Yb1':3, 'Yb2':3, 'Yb3':3}

cif_pc_model.IonLabel = 'Yb2'

cif_pc_model.Neighbour = 1

cif_blm = cif_pc_model.calculate()

print(cif_blm)

Note that only the magnetic structure (as a CrystalStructure object, CIF file name or workspace) is needed

to construct a PointCharge object. However, the calculations will return an error unless both IonLabel

and Charges are defined. By default a value of 5  for MaxDistance is used if neither

MaxDistance nor Neighbour is defined. Whichever of MaxDistance or Neighbour is defined last

takes precedent, and if both are defined in the constructor, e.g.:

for MaxDistance is used if neither

MaxDistance nor Neighbour is defined. Whichever of MaxDistance or Neighbour is defined last

takes precedent, and if both are defined in the constructor, e.g.:

bad_pc_model = PointCharge('AMS_DATA.cif', MaxDistance=7.5, Neighbour=2)

then the value for MaxDistance will be used regardless of where it appears in the keyword list.

For Charges, instead of listing the charges of each site, you can just give the charge for each element, e.g.:

cif_pc_model.Charges = {'O':-2, 'Yb':3}

cif_blm = cif_pc_model.calculate()

The result of the calculate() method can be put directly into a CrystalField object and used either to calculate a spectrum or as the starting parameters in a fit:

cf = CrystalField('Yb', 'C2', Temperature=5, FWHM=10, **cif_pc_model.calculate())

plot(**cf.getSpectrum())

fit = CrystalFieldFit(cf, InputWorkspace=ws)

fit.fit()

Finally, note that the calculated crystal field parameters are defined with the quantisation axis along the z direction in the Busing-Levy convention (that is, it is perpendicular to the a-b plane). This means that if the particular magnetic ion lies on a higher symmetry site but the highest symmetry rotation axis is not along z (for example, the A or B site in the Pyrochlore lattice, which has a 3-fold axis along [111], whilst z is parallel to c), then the parameters may appear to have a low symmetry (e.g. more m terms are nonzero). You then need to rotate the parameters if you want it quantised along the high symmetry direction.

In addition to the inelastic neutron spectrum, various physical properties arising from the crystal field interaction can be calculated. These include the crystal field contribution to the magnetic heat capacity, the magnetic susceptibility, and magnetisation. The calculated values can be invoked using the getHeatCapacity(), getSusceptibility() and getMagneticMoment() methods.

To calculate the heat capacity use:

Cv = cf.getHeatCapacity() # Calculates Cv(T) for 1<T<300K in 1K steps (default)

pyplot.plot(*Cv) # Returns a tuple of (x, y) values

T = np.arange(1,900,5)

Cv = cf.getHeatCapacity(T) # Calculates Cv(T) for specified values of T (1 to 900K in 5K steps here)

pyplot.plot(T, Cv[1])

# Temperatures from a single spectrum workspace

ws = CreateWorkspace(T, T, T)

Cv = cf.getHeatCapacity(ws) # Use the x-values of a workspace as the temperatures

ws_calc = CreateWorkspace(*Cv)

plot(ws_calc, 0) # Creates workspace from data and plots it (plots the first spectrum, index 0)

# Temperatures from a multi-spectrum workspace

ws = CreateWorkspace(T, T, T, NSpec=2)

Cv = cf.getHeatCapacity(ws, 1) # Uses the second spectrum's x-values for T (e.g. 450<T<900)

plot(*Cv)

All the physical properties methods returns a tuple of (x, y) values. The heat capacity is calculated in Jmol-1K-1. The theory is described in CrystalFieldHeatCapacity.

The molar susceptibility is calculated using Van Vleck’s formula, and requires in addition knowledge of the applied field direction (default is [0, 0, 1] where the field is along the crystal field quantisation direction):

chi_v = cf.getSusceptibility(T, Hdir=[1, 1, 1])

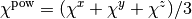

The field direction is a Cartesian vector with coordinates defined with the z-axis parallel to the quantisation direction of the crystal field parameters (usually taken to be the highest symmetry rotation axis). To calculate for a powder averaged field direction use:

chi_v_powder = cf.getSusceptibility(T, Hdir='powder')

The powder averaging is done by taking the mean of the susceptibility (or magnetisation) along the  ,

,

and

and  directions (e.g.

directions (e.g.  ).

).

Note that the function calculates the molar magnetic susceptibility, and by default outputs it in cgs units (cm3/mol or emu/mol). To obtain the result in SI units (m3/mol) use:

chi_v_cgs = cf.getSusceptibility(T, Hdir=[1, 1, 0], Unit='SI')

In addition, “atomic” units ( ) can also be obtained using:

) can also be obtained using:

chi_v_bohr = cf.getSusceptibility(T, Unit='bohr')

The theory is described in the CrystalFieldSusceptibility function page.

The magnetic moment is calculated by adding a Zeeman interaction to the crystal field Hamiltonian and diagonalising the combined matrix, from which the expectation of the magnetic moment operator is calculated. The moment can be calculated as a function of temperature or applied field magnitude:

moment_t = cf.getMagneticMoment(Temperature=T, Hdir=[1, 1, 1], Hmag=0.1) # Calcs M(T) with at 0.1T field||[111]

H = np.linspace(0, 30, 121)

moment_h = cf.getMagneticMoment(Hmag=H, Hdir='powder', Temperature=10) # Calcs M(H) at 10K for powder sample

By default, the magnetisation is calculated in atomic units of bohr magnetons per magnetic ion. Alternatively, the SI or cgs molar magnetic moments can be calculated:

moment_SI = cf.getMagneticMoment(H, [1, 1, 1], Unit='SI') # M(H) in Am^2/mol at 1K for H||[111]

moment_cgs = cf.getMagneticMoment(100, Temperature=T, Unit='cgs') # M(T) in emu/mol in a field of 100G || [001]

Please note that if cgs units are used, then the magnetic field must be specified in Gauss rather than Tesla (1T == 10000G). Note also that the cgs unit “emu/mol” in this case is “erg/Gauss/mol” quantifying a molar magnetic moment.

Finally, please note that the calculation result is the molar magnetic moment. Thus to get the magnetisation, you should divide this by the molar volume of the material. By default, the calculation temperature is 1K, and the applied magnetic field is 1T along [001]. For further details and a description of the theory, see the CrystalFieldMagnetisation and CrystalFieldMoment pages.

Instead of fitting the inelastic neutron spectrum, the physical properties can be fitted using a similar interface to that described above. The main difference is that some experimental setup information has to be given - especially for the susceptibility and magnetisation. This is done by specifying an instance of the PhysicalProperties helper class as the PhysicalProperty attribute of CrystalField, either as a keyword argument in the constructor:

from CrystalField import CrystalField, CrystalFieldFit, PhysicalProperties

# Fits a heat capacity dataset - you must have subtracted the phonon contribution by some method already

# and the data must be in J/mol/K.

cf = CrystalField('Ce', 'C2v', B20=0.37737, B22=3.9770, B40=-0.031787, B42=-0.11611, B44=-0.12544,

PhysicalProperty=PhysicalProperties('Cv'))

fitcv = CrystalFieldFit(Model=cf, InputWorkspace=ws)

fitcv.fit()

or separately after construction:

cf = CrystalField('Ce', 'C2v', B20=0.37737, B22=3.9770, B40=-0.031787, B42=-0.11611, B44=-0.12544)

cf.PhysicalProperty = PhysicalProperties('Cv')

fitcv = CrystalFieldFit(Model=cf, InputWorkspace=ws)

fitcv.fit()

# Fits a susceptibility dataset. Data is the volume susceptibility in SI units

cf.PhysicalProperty = PhysicalProperties('susc', Hdir='powder', Unit='SI')

fit_chi = CrystalFieldFit(Model=cf, InputWorkspace=ws)

fit_chi.fit()

# Fits a magnetisation dataset. Data is in emu/mol, and was measured at 5K with the field || [111].

cf.PhysicalProperty = PhysicalProperties('M(H)', Temperature=5, Hdir=[1, 1, 1], Unit='cgs')

fit_mag = CrystalFieldFit(Model=cf, InputWorkspace=ws)

fit_mag.fit()

# Fits a magnetisation vs temperature dataset. Data is in Am^2/mol, measured with a 0.1T field || [110]

cf.PhysicalProperty = PhysicalProperties('M(T)', Hmag=0.1, Hdir=[1, 1, 0], Unit='SI')

fit_moment = CrystalFieldFit(Model=cf, InputWorkspace=ws)

fit_moment.fit()

Unfortunately only 1D datasets can be fitted (e.g. M(H, T) cannot be fitted as a simultaneous function of field and temperature). Also, note that setting the PhysicalProperty attribute after constructing the CrystalField object (e.g. running cf.PhysicalProperty = PhysicalProperties(‘Cv’)) causes the number of datasets to change and will clear all Ties and Constraints previously set, and also reset all FWHM and peaks to the default values (zero for FWHM and Lorentzian for peaks).

Finally, physical properties data and neutron spectra may be fitted simultaneously. In this case, all the inelastic neutron spectra must be specified first in the list of input workspaces, with the physical properties dataset(s) following in the same order as specified in the PhysicalProperty attribute, which for multiple physical properties should be a list. E.g.:

# Fits an INS spectrum (at 10K) and the heat capacity simultaneously

cf = CrystalField('Ce', 'C2v', B20=0.37737, B22=3.9770, B40=-0.031787, B42=-0.11611, B44=-0.12544)

cf.Temperature = 10

cf.FWHM = 1.5

cf.PhysicalProperty = PhysicalProperties('Cv')

fit = CrystalFieldFit(Model=cf, InputWorkspace=[ws_ins_10K, ws_cp])

fit.fit()

# Fits two INS spectra (at 44K and 50K) and the heat capacity, susceptibility and magnetisation simultaneously.

PPCv = PhysicalProperty('Cv')

PPchi = PhysicalProperty('susc', 'powder', Unit='cgs')

PPMag = PhysicalProperty('M(H)', 5, [1, 1, 1], 'bohr')

cf = CrystalField('Ce', 'C2v', B20=0.37737, B22=3.9770, B40=-0.031787, B42=-0.11611, B44=-0.12544,

Temperature=[44.0, 50], FWHM=[1.1, 0.9], PhysicalProperty=[PPCv, PPchi, PPMag] )

fit = CrystalFieldFit(Model=cf, InputWorkspace=[ws_ins_44K, ws_ins_50K, ws_cp, ws_chi, ws_mag])

fit.fit()

Note that PhysicalProperty requires the type of physical property (either ‘Cv’ or ‘Cp’ or ‘heatcap’ for heat capacity; ‘susc’ or ‘chi’ for susceptibility; ‘mag’ or ‘M(H)’ for magnetic moment vs applied field; or ‘mom’ or ‘M(T)’ for moment vs temperature) as the first argument. subsequent arguments are optional, and are in the following order:

PhysicalProperties('Cp') # No further parameters required for heat capacity

PhysicalProperties('chi', hdir, inverse, unit)

PhysicalProperties('chi', unit)

PhysicalProperties('mag', hdir, temp, unit)

PhysicalProperties('mag', unit)

PhysicalProperties('M(T)', hmag, hdir, inverse, unit)

PhysicalProperties('M(T)', unit)

Or these parameters may be specified using keyword arguments, with the keywords: ‘Hdir’, ‘Hmag’, ‘Inverse’, ‘Unit’, and ‘Temperature’ (note these are case sensitive, and not all parameters apply to all types of physical properties). The default values (Hdir=[0,0,1], Hmag=1, Inverse=False, Unit=’cgs’ and Temperature=1 are used if nothing is specified for a particular attribute.

Categories: Interfaces | Indirect